Revenue Reform Resources

Overview

LOC’s Board of Directors has funded efforts to study the viability of revenue reforms, including changes to the property tax system. Municipalities find it challenging to keep up with the rising cost of providing services when property tax revenues—usually their main funding source—are restricted from growing as quickly. To address this, LOC tasked a group of local experts and a consultant team to explore potential reforms and assess whether meaningful reform is possible. LOC hosted focus groups, conducted public opinion research and created the Oregon Local Revenue Tools Guidebook. This guidebook builds on insights and themes from the 2024 revenue reform research process. While the guidebook’s main purpose is to summarize public information about revenue options available to Oregon cities, it is informed by findings from community focus groups and surveys from related policy research. Some key findings informing this guidebook include the following:

- Many Oregonians believe the property tax system is outdated and does not work well.

- They are cautious about changes that could raise their taxes.

- Oregonians generally believe municipal revenues are sufficient to provide ongoing city services.

- Public support is greater for targeted changes, especially those that tax new developments, visitors and tourists, and large businesses.

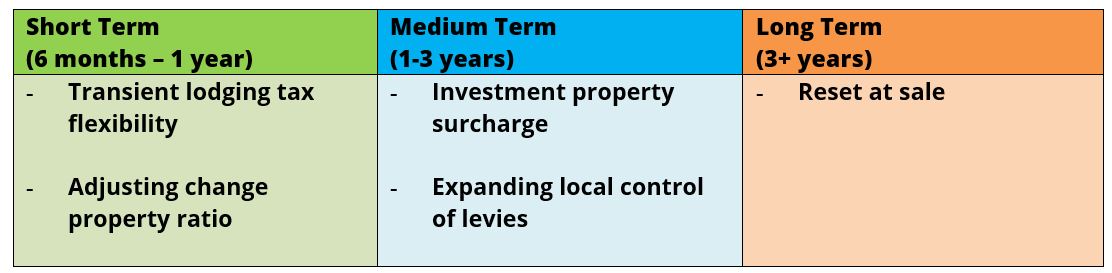

The LOC Board of Directors received consultant recommendations at their December and January meetings outlining general and policy recommendations. Policy recommendations are separated into short, medium and long-term goals.

The LOC Finance Committee is developing a multi-year funding strategy for the next phases of revenue reform project.

Background on Need for Revenue Reform

Oregon adopted an income tax in 1930 to replace a state property tax. Efforts to establish a state sales tax have failed nine times at the ballot since 1933, with the “no” vote exceeding 70% of voters. General local sales taxes have failed too. Cities, counties, and school districts had relied heavily on property taxes to fund services. Before the 1990s, local governments built a budget and spread out the cost among property owners in their jurisdiction. This “levy-based” tax system often created large changes year over year for taxpayers But, in 1990, Measure 5 established caps on property taxes: $10 per $1,000 of property value for general government and $5 per $1,000 of property value for education services. Tax collections dramatically fell for many jurisdictions. The state legislature stepped in to address the shortfall in education funding. In 1997, voters adopted Measure 50 to make property taxes predictable and separated the property tax from market values. Each year, county assessors could increase the assessed value by up to 3 percent if it remained lower than the property’s real market value. The total cap from Measure 5 remained in place. Because of these property tax limits, the property tax revenues for Oregon cities grow more slowly than market values and, in many years, the rising cost of service.